Intro

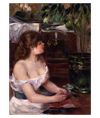

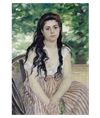

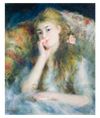

Light, sensual, and charming: the Impressionist paintings of Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919) are instantly recognizable. Dubbed the “painter of happiness”, Renoir remains as famous as ever for his café scenes and sensitive portraits. Renoir is known as a modernist painter, but that certainly doesn’t mean he was no longer inspired by the art of the past. Decorative and dynamic, powdery pastel-like and dreamy, the forms, colors, and motifs of the 18th century Rococo style can be reencountered in Renoir’s world of pastime and pleasure.